| ||||||||||||

"

Our mind is capable of passing beyond the dividing line we have drawn for it. Beyond the pairs of opposites of which the world consists, new insights begin."-Herman Hesse

From The Book:

Everything Forever:

Learning to

See Timelessness

"The One has never

known measure and stands outside of number, and so is under no limit either in regard to anything external or internal;

for any such determination would bring something of the dual into it."

—Plotinus

"In our life there

is a single color, as on an artist’s palette, which provides the meaning of life and art. It is the color of

love."

-Marc Chagall

"If

one feels the need of something grand, something infinite, something that makes one feel aware of God, one need not go

far to find it. "

-Vincent Van Gogh

"A

single consciousness, a universal wisdom, pervades the universe. And more than that. The discoveries of science, those

that search the quantum nature of subatomic matter, have moved us to the brink of a startling realization: all existence

is the expression of this wisdom. In the laboratories we experience it as information that first physically articulated

as energy and then condensed into the form of matter. Every particle, every being, from atom to human, appears to

represent a level of information, of wisdom."

-Gerald Schroeder

Physicist

"

The depth of our penetration into the problem is measured not by the state of things on the frontier but rather how far away the frontier lies. One of the most pronounced examples of such a situation concerns beyond any doubt the nature of time. What we have precisely in mind here is a puzzling discrepancy between our perception of time and what modern physical theory tells us to believe"--Metod Saniga

"

There are of course two well-known "axes" in music. They are absolutely fundamental to all forms of music.1. Melody. This represents the horizontal axis. Notes occur one after the other in temporal sequence which creates "melody" or "line". The patterning of notes and rhythms gives rise to groupings which are used to advance the structure of the melody by a patterning effect. Melodic processes represent the tendency of musical ideas to "clump" or impinge on the imagination via "cells" or "motifs" or "hook phrases".

2. Harmony. This is the vertical axis of music. This represents the combination of all sounds, voices, instruments, timbres, notes that are active in the music at any one moment. A harmony can be like a chord, or merely the summation of a vertical texture comprising many elements. The important thing about a harmony is that all the elements that comprise it are no longer perceived as distinct from each other. Harmony brings about symmetry order by introducing the process whereby notes lose their distinctness and blend to form an overall texture that could be labeled opaque. We say that "harmony accompanies melody" which draws attention immediately to the two different ordering processes."

--Kim Jones

Composer

Recommended Site:

Suggested Reading:

The

Equation that Couldn't be Solved:

How mathematical Genius

Discovered the Language of Symmetry

Mario Livio

(A lot of interesting parallels between this book and Everything Forever)

|

Advanced Study

Grouping

and Symmetry (From

Chapter 6

- Natural Order)

Life is acutely tuned to the discovery of order. It is our nature to develop structures and organize, categorize and store. It is also our nature to strive for beauty. We gravitate toward the arts, judging the complexities of music and painting, sometimes not knowing anything more than how it makes us feel. The artist tunes into the open world of possibilities searching for ways of combining patterns and colors that triggers interest in the mind of the observer. We can recognize now that it is some complex combination of grouping and symmetry which we are attracted to in art, architecture, and the artistry of nature. In the wide range of human-made visual art there are compositions more toward the nature of grouping order that emphasize the order of definition and form, by being realistic, distinct, and bold, from artists such as Michelangelo, Picasso, or Salvador Dali. And there are compositions in which distinctiveness and boldness is traded for showing the connectedness and commonality between things, where objects flow together, where a unity is felt, as found in paintings from Vincent Van Gogh or Winslow Homer.

Figure 1: Comparing the bold pronounced work of Rembrandt with the flowing low-contrast unity of Van Gogh. The composition of a painting can be more variegated and distinct or it can be more uniform and flowing. Colors of a painting can blend smoothly or they can stay pure and sharp in contrast. Works toward the nature of symmetry order are often low contrast with blended colors and wide brush strokes. Generally speaking, the overall expression of a painting can either be more uniform and flowing or it can be more variegated and distinct. Paint colors can blend smoothly or they can stay pure and sharp in contrast. Each of the different mediums in art, such as watercolor or inks, express either the unity of the world or the distinction of things. Watercolor paintings overlap and flow together while ink pen drawings are contrastive with sharp lines and distinct shapes. This range of possibilities we are comparing is the two directions of order governing both materials and composition. There are artists who in exploring composition have learned to recognize and utilize two orders at an intuitional level years ahead of science. Some art work seems to capture the rules of the unseen underlying orders, especially visible in the woodcut prints of Charles Beck. In Beck’s art we see a rigid combination of grouping and symmetry. Generally in Beck’s work, distinct subjects are spread almost perfectly even in the painting, like rhythm in music, sometimes with the only asymmetric element being a trace of human activity taking place among the combining of grouping and symmetry. In his art Beck often seems to convey an intuited awareness of our place in nature between the two orders.

© Charles Beck Maplelag & Poplars Figure 2: Woodcut Prints of Charles Beck visually reveal the two orders cooperating. In Beck’s prints, objects or things are portrayed evenly and symmetrically and although the evenness of the trees and the buildings might be increased to an even greater extreme, they would then appear so orderly that they would not convey the message. They would not relate in a mysterious way to similar patterns we see in nature. In nature we commonly see things combined together evenly although the evenness is less rigid and distinct than what artists often portray. Artists often add-in or choose a point of view that frames greater symmetry, since we all enjoy symmetry. Beck’s landscape compositions above compared to those below communicate that we are constantly witnessing balance and symmetry in nature, it is just a less rigorous and exacting symmetry.

Figure

3: Similar scenes in nature show a less tense combination of two The Axis of Orderliness to Chaos What is the difference between the beauty we see in nature and the artistic beauty we see in man-made creations? The difference between common patterns in nature apart from those patterns that are constructed intelligently by humans as seen in art and architecture is understandable as a variable of the tension between the two orders. A carefully planned intelligent design can increase this tension until the two orders begin to cooperate to create orderliness and complexity. Opposite to cooperation there is randomness. Normally the definition of randomness means to have no specific pattern or objective, and randomness creates disorder, chaos, and disorganization, however, randomness is understandable as a measure of freedom that only exists between the two orders. The extremes of grouping and symmetry orders are very strict. Each part cooperates with other parts to create a whole pattern that is highly ordered. A random pattern is the opposite case where the parts of a pattern do not cooperate with one another. The ordinary patterns we experience in nature are always created only by two orders, but most patterns in nature are less intensely symmetrical or less intensely grouped than man-made patterns, so there is a randomness or freedom in the pattern, which is still the two orders working together, but not as intensely or synchronically as is possible. In comparison, man-made creations can fuse the two orders together in a way that eliminates randomness. A checkered pattern for example includes both grouping and symmetry in a very strict way. Such a pattern is possible only if each order is intensely cooperating, while the two orders are also combined together and so competing against one another. A calico pattern shows a less intense measure of competition between both orders, yet we still can see the cooperation of each order, with grouping order creating distinct round objects, and symmetry order spreading those objects evenly.

Figure 4: In the transition from grouping to symmetry order

nature does

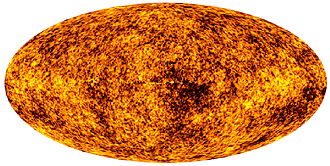

In the checkered lattice pattern above we can easily recognize orderliness and complexity where in the calico pattern we are seeing more freedom and irregularity. Such patterns portray the spectrum from order to disorder that we normally imagine applies to all patterns, however, this spectrum is only one of three fundamental axes. The first axis runs between the Alpha state of the big bang and absolute zero or Omega. The second axis exists adjacent the first and spans between extreme contrast and zero contrast. Then adjacent the second axis there exists a third axis spanning from extreme orderliness (such as the checkered lattice shown above) to the calico pattern, then further to extreme disorder and chaos. The three fundamental axes are presented more fully and displayed graphically in part three. Seeing Two Orders in All Patterns Hypothetically speaking the conditions of our own universe could travel toward extremes, but that is not what we observe. The expansion of the universe is moving conditions away from Alpha and ever nearer to absolute zero in a very steady and consistent manner. The universe stays very balanced between the extremes of lumpy and smooth, and we observe a mild level of orderliness throughout the cosmos as opposed to extremely high orderliness or extreme chaos.

Figure 5: Above the universe over 13 billion years ago as represented by the microwave background radiation measured by the WMAP Satellite revealing regional lumpiness in the early universe before galaxies had formed (images from NASA), and below, a small sampling of the distant galaxies that early lumpiness became (HST Abell Cluster).

There is an increased orderliness in patterns at low temperatures, first seen in things such as window frost or a snow flake, but in warmer climates we commonly observe a measure of freedom or irregularity, which is essentially a measurable weakness in the influence of the two orders, in contrast to a man-made fractal which displays an extremely intense combination of two orders.

Figure 6: The uniformity of water vapor in clouds and in the air and symmetry in the chemical structure of water translates into the complex symmetry of a snowflake. Fractals exhibit intense symmetry. Usually we draw a line between patterns in nature and patterns that are man-made, as if man isn’t natural, but the only real difference is the combined intensity of each order. Intense competition creates a level of cooperation in what can be called an order game, or some way in which the two orders are intelligently made to work together. Human beings play all sorts of order games where the two orders directly compete against one another, most plainly in sports, card and board games (especially checkers), but also in social situations, business, politics, and conflicts such as war. It doesn’t take long before a person is able to recognize grouping and symmetry in all patterns, both natural and man-made. If we analyze the images below as an exercise of finding cooperation between two orders, in the first photo, clouds of fog float through a recognizably even distribution of trees in a forest. A cloud of fog is a group of particles, although there is an obvious symmetry in the distribution of the particles within the cloud. Also this photo displays an "S" curve to the fog, well known to be an attractive pattern in art and photography because it has symmetry, true also of spirals. To the right, the growth of a plant exhibits obvious symmetry while the rain drops are grouped on particular leaves. Next, even in this irregular growth of trees there is a measure of evenness in the distribution of the trees and branches, difficult to appreciate as order, yet there is symmetry order in this image, although it is more evident in the even distribution of fallen leaves. Below left, grooves carve up the earth evenly and seedling plants sprout along each row evenly, forming the group of each row, and here we easily appreciate the symmetry of the collective rows. Mountains in this satellite image of the Himalayas each represents grouping order, particularly Everest, but from afar we see the collective uniformity of the mountains.

To focus more clearly on what we perceive as beauty we can turn to the less temporary art of architecture. We most commonly find an intense competition between grouping and symmetry in man-made designs of governmental and religious architecture. The pronounced grouping of materials contrasting the even distributions of windows and columns are easily recognized in these buildings, as well as the general bilateral symmetries. All these symmetries are components of a balance showing little sign of the innate conflict with the grouping order nature of the buildings themselves. Yet take away the symmetries and we would have a simple pile of matter. Obviously it is pronounced masses ornamented with symmetries that we find to be beautiful in architecture, likewise true of sculpture, music, art and nature.

Figure 8: These great landmarks show the human preference for both orders combined together intensely competing and yet cooperating. Of course we forget sometimes that literally everything that exists is of the natural world. All that human beings create is part of the universe and so nature. The only imaginable distinction between nature and the human world is that we humans can intelligently make the two orders cooperate in ways that nature cannot accomplish without our help. This does not mean however that there isn’t an equal measure of cooperation occurring generally in nature. We might even ask, when we consider patterns in general, is there a greater measure of cooperation in human-made patterns over natural patterns? Note that most human-made patterns are not as rigidly perfect as the architectural examples shown, while many plants and animals rival our creations with exquisite orderliness. There are likely consistent measures of chaos and cooperation at all levels everywhere in the universe, even at the human level, almost as if we accomplish exactly what nature has designed into us.

Two Orders in Sound and Music Near the turn of the century the art philosopher George Lansing Raymond struggled to understand the common underlying structure of order as it exists in art, music, and poetry as equally as it exists in nature. In The Genesis of Art Form Raymond writes:

Grouping and symmetry provides a simple way of understanding the common order of all patterns in nature including art and music. In separating grouping and balance into two components the complexities of art and the harmonies of music are perhaps more fundamentally comprehensible than with any other method of description. The first level of grouping order in music is just a single note breaking silence, like a particle in space, or a star in the sky. Then in the rhythm of music we find the evenness and balance of symmetry order. Often in a song several different notes are played simultaneously with one instrument to create a chord, which is somewhat like cooking various vegetables into a soup. A careful selection of certain like notes create harmonious chords, just as many different instruments create songs.

In the same way that we can define a frame of reference in space, we can define a frame of reference in time, which in music is called a measure. A musical example we can pick apart which most everyone is familiar with would be the first notes of Beethoven's fifth symphony. Three sudden notes are followed by a drawn out fourth note. A series of pronounced individual notes played close together as opposed to further apart in time is of course intense grouping order, although the even rhythm is symmetry order. A steady rhythm is perhaps the most important ingredient of music. Rhythm is what distinguishes music apart from all other sound. But we also find symmetry in a lasting note duration, which is like a smooth dense space in which matter is spread evenly. The complex ordering of many musical instruments can be interesting, pleasant, saddening, spirited and exciting, able to compliment and enhance every human emotion, perhaps suggesting a connection. Musical instruments create either more pronounced blunt sounds akin to grouping order, as with percussion instruments such as drums. Other instruments play sustained notes and chords more evenly across a measure of time, such as a violin or a flute, representing symmetry order. Music genres like rock and roll or rap that are pronounced with a strong beat are more of the nature of grouping order, while the smooth and drawn out rhythms sometimes produced by a symphony are more toward the nature of symmetry order. Regardless, a beautiful musical composition resonates with both the distinction of notes and instruments, and the limited harmonizing of those notes and instruments.

Figure 9: Multi-tracks of regular sounds. Raymond, who was a professor of aesthetics at Princeton, also considered how two very basic but very different elements contribute to the beauty of art and music. Raymond initially focuses on the role of “likeness”.

The likenesses mentioned of lyrics

and poetry are most apparent in very simple poems such as, “Mary had a little lamb, its fleece was white as snow. And

everywhere that Mary went, the lamb was sure to go.” But specifically what does Raymond mean by likeness. How many

different ways can things be alike? Are there perhaps opposing directions that things can be alike? For example, each

letter in the alphabet is different, yet some letters form a group called vowels, which are alike in ways but different

than the group of consonants. And yet all are alike in simply being letters, so letters are simultaneously different and

alike. Where letters are expressions of distinct form and thus grouping order they are different, and where letters are

a general type of forms they are alike, and as a whole create a uniformity. It can be a surprise to realize that all the

letters It is said that someone asked Michelangelo how he had created such a perfect image of David out of stone, to which he replied that David was there in the stone all along, and just needed a little help in getting out. In being so focused upon likenesses that establish the differences we notice between things, which make classification possible, we easily forget that everything is of a single existence and thus is ultimately just one thing. Ultimately all difference is an illusion. All things are ultimately alike. Is the beauty of music and poetry and art determined by a mix of these two opposite directions of likeness? Having considered likeness, Raymond then focuses on variety and contrast:

In how likeness in one way makes things different and classifiable, and in another way makes all things the same, we can see distinctly why there are two different and incompatible kinds of order in nature. In one direction of being alike things are different and unlike other things. Birds of a feather flock together. This classification creates contrast and unlikeness. Unlikeness is even required of diversity. In another direction of being alike things are more general or similar to other things. All birds are mammals. All mammals are animals. All animals are life forms. All forms are matter. All matter is part of one great existence. In combining like with like we create the distinctions and definitive form of grouping order, yet in combining that same unlikeness we somehow further the unity of symmetry order. We bring all things together into a whole. We are all attracted to symmetries and balance in music and art, yet unlikeness and imbalances are a critical ingredient of the aesthetics of all art and music. Too much symmetry, too much harmony, too much balance, and we end up with silence. No matter how intense, a synchronized positive wave and a negative wave turn each other into silence. And to us, silence, like the white canvas, is boring.

Figure 10: When two sounds are perfectly out of phase they combine into silence. The more the notes and chords are drawn out, the more the music is indistinct and unified over its measure of time, and here again the extreme moves toward a single sound that cannot be heard. Sound is fundamentally an oscillation. Without oscillation, sound is silence. Sound, like both energy and matter, is an oscillation of waves, and when we stretch that wave flat it becomes silence. Flat sound, flat energy, flat matter, is like the color white, our senses perceive it as a nothing even though all possible sounds combined together have the same consequence. All music is created from limited measures of imbalance and balance. In music, in art, in poetry, we want to experience imbalances and balances eloquently woven together. We want the imbalances of grouped likenesses combined with the sameness and balance of symmetry. We want to see and hear the complexities possible in the myriad of ways of combining grouping and symmetry. We are attuned to those complex combinations possible of both orders. It isn’t simply order out of chaos that gives art and music its pleasurable qualities, it is the cooperation of each order in strict competition with one another.

Summary The distinction between the two kinds of order, between dividing things apart and mixing things together, initially seems too simple to be of any great importance. Certainly, the important simple principles have all been discovered long ago. It is after all something a child could understand. How can something so simple dramatically change how a person sees the complex world? Indeed the distinction between the two orders is simple, but our existing definition of order is even simpler than what is being explained. Consequently the concepts of order and disorder only vaguely describe the patterns we experience, which actually makes the universe seem more complex and perplexing than it is. After learning to recognize two orders virtually everywhere we look, we can try to return to the basic concepts of order and disorder, except an increase in symmetry order now means that grouping order is lost, and an increase in grouping order requires that symmetry order is decreased. This completely contradicts the commonly held belief shared by most that order decays into disorder and it contradicts the belief in science that there is high order in the direction of our past which is decaying in the direction of our future. The exclusivity of two orders necessarily replaces the commonplace concepts of order and disorder, showing that neither concept can be generally applied to nature. In essence, we have to start over. One more Advanced Page on Two Orders: The Absence of One Order Creates the Other Or move forward to map all possible universes.

Part Three : The Space of All

Possibilities This essay last updated Mar 7th, 2007 | |||||||||||||

| Your welcome to send an e-mail and share your thoughts when you're done reading. |

|

Homepage | Part One | Part Two | Part Three | Part Four | Part Five | Contents | Backward | Forward | |

|

© Gevin Giorbran, Copyright 1996 - 2007 All rights reserved. Privacy Policy | Usage Policy |

|

|